In conventional trusts, the trustee generally have a high level of control over the trust asset and the settlor has no rights left in respect of the trust asset. However, many settlors are not comfortable with the idea of handing over complete or exclusive control over their asset to another party.

Arising from this, a number of jurisdictions have formalised what are often referred to as reserved powers trust. Specific legislations had been enacted to ensure that settlor’s reserved powers arrangements can be put in place without prejudicing the validity of the trusts themselves.

INTRODUCTION

When a settlor establishes a Reserved Powers Trust, he may retain for himself, or confer on a third party, certain rights and powers. Most commonly, these include:

- the power to appoint and remove investment managers or brokers; and

- powers of investment.

A number of jurisdictions permit the reservation or grant of such powers without invalidating the trust, including Jersey, Guernsey, Singapore, Labuan and the Cayman Islands. However, the position in Singapore is more limited. Under Singapore law, reserved powers must be retained by the settlor personally and cannot be granted directly to a third party. While the settlor may subsequently delegate the exercise of those powers (for example, to an external investment manager), the legal reservation of the powers must remain with the settlor. This contrasts with other jurisdictions, where such powers may be reserved to, or vested directly in, a third party such as a protector or investment manager from the outset.

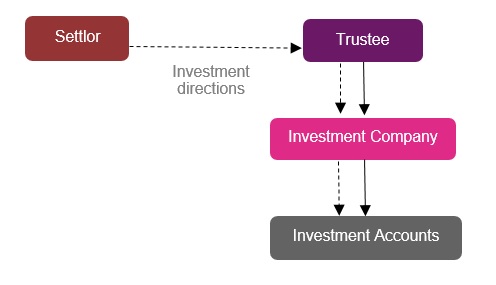

Example 1: Power to give investment directions

Included in the trust deed is an express power for the Settlor to give investment directions to the Trustee (usually only for as long as the Settlor is not under any incapacity).

Example 2: Power to effect investments

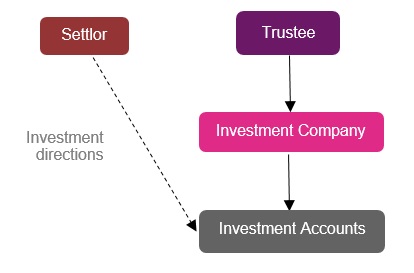

Under this approach, the trust deed includes a provision enabling the Settlor to direct the Trustee to issue to him a limited trading power of attorney, enabling him to effect investments.

As with the first example, the Trustee’s own powers of investment are "suspended".

This may be a better arrangement compared to the first example as the Settlor may deal directly with the broker in effecting investment transactions, and without being deemed an agent of the Trustee. The substantive sham risk is likely to be reduced because the trust deed more closely reflects how the trust is to be administered in practice.

CONCLUSION

There are good reasons why settlors who are more knowledgeable and sophisticated, and demand a more active involvement in investment decisions would want to reserve powers over the trust. Trustees are increasingly recognising the potential advantages of structuring trusts as reserved power trusts rather than as fully discretionary trusts, in appropriate cases.

However, the degree of settlor’s control has to be balanced against the fundamental concept of trust.